The Innovators of MycoHAB

- Robin Bacon

- Dec 19, 2023

- 4 min read

“Can’t we make mycomaterials and grow food at the same time?” — Chris Maurer

The United States has 17.4% of arable land, while locations like Namibia, located in the southwest of Africa, have just 1%. This statistic got me thinking about arable versus cultivated land; we have many terms to navigate in agriculture, whether it be irrigated versus non-irrigated, fallow, or pasture. Thinking about arable land, we know it’s either temporarily fallow or sometimes in a regeneration cycle. That arable land can be cleaned up and regenerated, taking the woody mass, macerating it, and recycling it for a more meaningful purpose. When I met Chris Maurer, principal architect with redhouse studio based in Cleveland, Ohio, I had many questions about his work in construction and mycotechnologies. He and a team of scientists and developers were asked to help remove 300 million tons of Encroacher Bush in Namibia. They are turning agricultural waste into food and construction by-products. This project blew my socks off!

The Backstory

Decades of drought and overgrowth of the Encroacher Bush or Acacia, choking out natural aquifers in the desert, have forced Namibia to rethink its agricultural and livestock management practices. Livestock farmers and agriculturists are dealing with an indigenous woody plant species overutilizing an already compromised water supply in the savannahs of southwest Africa. When Chris and his colleagues from MIT and Standard Bank began to evaluate and prioritize what could be done to solve an ecological and agricultural waste problem, they started with removing the Encroacher Bush and repurposing the waste into a mycotechnology program.

The Encroacher Bush was the genesis of a circular economy and business plan to create a fully linked supply chain while using the woody mass and concepts of mycotechnologies spawning new product development from the one causing environmental problems and, in this case, community displacement. The demand for sustainable protein is growing, and mushrooms are a big part of high-protein supplements, teas, and meat alternatives. To that end, mushrooms can be used to build a whole new source of protein while creating a new market for resident workers displaced from other agricultural workforces. Together, the team of scientists, farmers, and construction professionals began working to build a fully sustainable and extensible model called MycoHAB.

Building A Closed Loop System

Once the team sorted out the water and food security model, they laid the groundwork for housing, designed the layout and required materials, and implemented ecological considerations into the platform. Chris and his team created the design with a holistic approach to building with minimal construction waste.

Mushroom Farming - Construction Material Required

After the Encroacher Bush waste is harvested from the desert, it must be macerated and wetted for optimal use. Instead of making compost, Chris and the team took it two steps further. First, make food; second, use the waste from making the food by-product into composite building materials. They use the waste, filling it into bags, steaming and sanitizing those bags of woody mass, creating a substrate from which the mycelium spawn is grown. Once the “grow cycle” ends, the mushroom waste can be prepared into a more robust construction material. The team decided to take the substrate from mushroom production, using the mycelium or the root structure of fungi to make composite blocks and other construction materials once the mushrooms are fruited and harvested.

Using recycled shipping containers for growing houses, the mycelium spawn is fed into the substrate for fruiting, allowing germination, colonization, and total mycelial expansion into the mushroom bag. The process takes around 30 days for the mycelium to fruit mushrooms. Once ready, the on-site agricultural workers harvest, clean, and distribute the product to the markets and wholesale buyers.

The leftover substrate, or mycelium composite, gets reused and taken through a process whereby it is poured into steel molds and then into a 200-ton steel press. Once pressed, the woody mass is baked into bricks. The high heat fuses mycelium and substrate together to strengthen the material. This material becomes fire-resistant, sound attenuating, structural, and insulative. Not only is a new product produced out of waste material, but it also meets the five tenets of creating a circular economy: circular supply, resource recovery, product life expansion, sharing, and creating a product service system model.

Circular Economy

Business models are changing - companies are subject to tremendous resource restraints and barriers to entry. Some organizations are pivoting and adapting to seeking materials with potential for positive, environmental, and social metrics. Business innovation aims to improve with limited risks and use of resources and experimentation through collective learning and collaboration. Eco-design and innovation are at the forefront of building a circular business model: adaptable, extensible, and flexible.

Producing Sustainable Construction Materials

Population growth is spiking, and the demand for new and alternative construction materials is on point with Chris’s mission of making a positive impact with humanitarian architecture and ecological innovation. To help solve these problems, mycotechnologies not only offer a solution to the construction industry but are also changing the way we ship perishable materials. Instead of using Styrofoam, we are adopting myco-composites in packaging.

Materials and methods are being evaluated at universities like MIT, Stanford, and Johns Hopkins. The team is working with scientists and civil engineers to determine whether these materials will meet or exceed construction industry standards. Regulation is very important when considering seismic characteristics and load balancing.

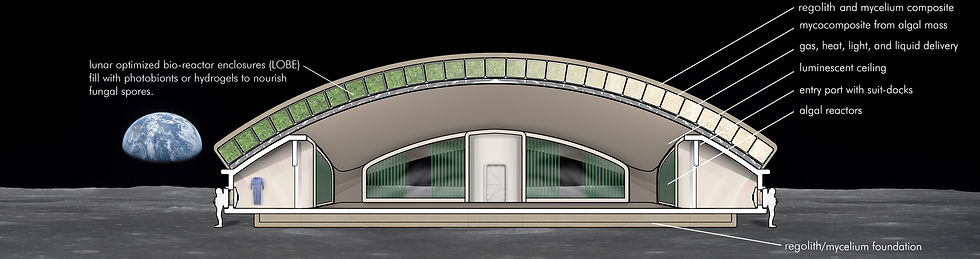

redhouse studio & The Red Planet Project With NASA Innovation

A more scientific application of using mycelium to create habitats is the NIAC - NASA Innovation & Advanced Concepts, where Chris took a brief detour to Red Planet Workshop before landing in Namibia. The Red House Studio team is working with Dr. Lynn Rothschild to prototype a self-inflating habitat on Mars. In conjunction with a Rover, the prototype will test the infusion of carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and water to feed algae within a sealed bag of mycelium. The structural mycelium fills the form, creating a pop-up livable shelter stronger than concrete.

Biocycler Lab

Chris and his team are continuously running new product design and development applications at their lab in Cleveland. They are working toward implementing cultured bio-binders to eradicate construction waste, otherwise used as landfill compaction. Their website is chock full of unique projects, concepts, and projects in design.

%20%20top%20vie.jpg)

Comments